Into the Gaza Envelope, 500 Days After the Massacre

Nothing could have prepared us to bear witness to such devastation in Otef Aza, the "Envelope" region dotted with kibbutzim within a few miles of Gaza.

Before making aliyah, an Israeli dad at our youngest kid’s Northern California preschool started telling me about his dream to move back to The Land. I asked him where exactly he would want to live, and he said, “Otef. Only the Otef. I wouldn’t live anywhere else.”

He was referring to the smattering of kibbutzim and other small communities nestled into large swathes of some of Israel’s most pristine agricultural land, which are also situated within perilous proximity to the Gaza strip. I had never been there, but I kept hearing from people that the kibbutzniks had created some sort of paradise - both in their cultivated environment, and also in their social culture - that radically outweighed the nuisance of frequent rocket attacks launched from Gaza, a few kilometers away.

The opportunity to get an insider perspective of these communities came the same way they always do here: someone calls with a spontaneous offer, and we immediately say yes. In this case, Orlee’s friend told us he was heading down to Kibbutz Be’eri and Nir Oz, two of the hardest hit, to monitor and report on philanthropic contributions from Canada to support the rebuilding effort. We would be received by people born and raised in each respective kibbutz, and walked through each community on a private tour.

As we drove through the rolling hills filled with orchards, wheat fields, flowers and solar arrays, it reminded me of the bucolic beauty of West Marin. The difference was that there were thousands of yellow flags flying, “Bring Them Home” billboards, and oftentimes we would pass over a high point and catch a glimpse of the haggard Gaza skyline, its deathly gray tones juxtaposed against the foreground of verdant Israeli farmland.

Rushing to arrive on time, we whizzed passed the Nova Festival site, which felt intimately familiar. The thinned out forests, the color palette, the curves of the roadways — the whole micro-geography had been indelibly lodged into my memory through all of the horrific videos. Minutes later, we arrived at Kibbutz Be’eri, fenced in and heavily guarded.

The relatively large 1,200-person kibbutz is organized like every other: a series of suburban-style streets with clusters of simple, well-maintained homes built with love-filled gardens, a central cheder ochel (dining room building), a preschool, playgrounds, and in this case, an industrial printing press factory that generates significant wealth for the collective, rather than for the individuals. At Be’eri, all resident workers earn the same modest income, from the gardener to the CEO of the commercial printing operation. They even have a fleet of shared cars rather than individually-owned ones. It is a social architecture almost unheard of in modern countries, and it makes for an unusually tight-knit Community, with a capital C.

Some years ago, one young kibbutz member was diagnosed with cancer, and the collective voted unanimously to pour millions of shekels into his medical care, without reservation. He ended up passing away, but the gesture sent a message to all members: we got you.

The young kibbutznik who walked us through the community told us that growing up, they would say that it is “99% paradise, and 1% hell.” On one hand, most of their time was spent in a veritable utopia; on the other, they would have 10 seconds to run into one of many dozens of bomb shelters peppering the property when sirens would sound — something that happened all the time, part of the rhythm of life there.

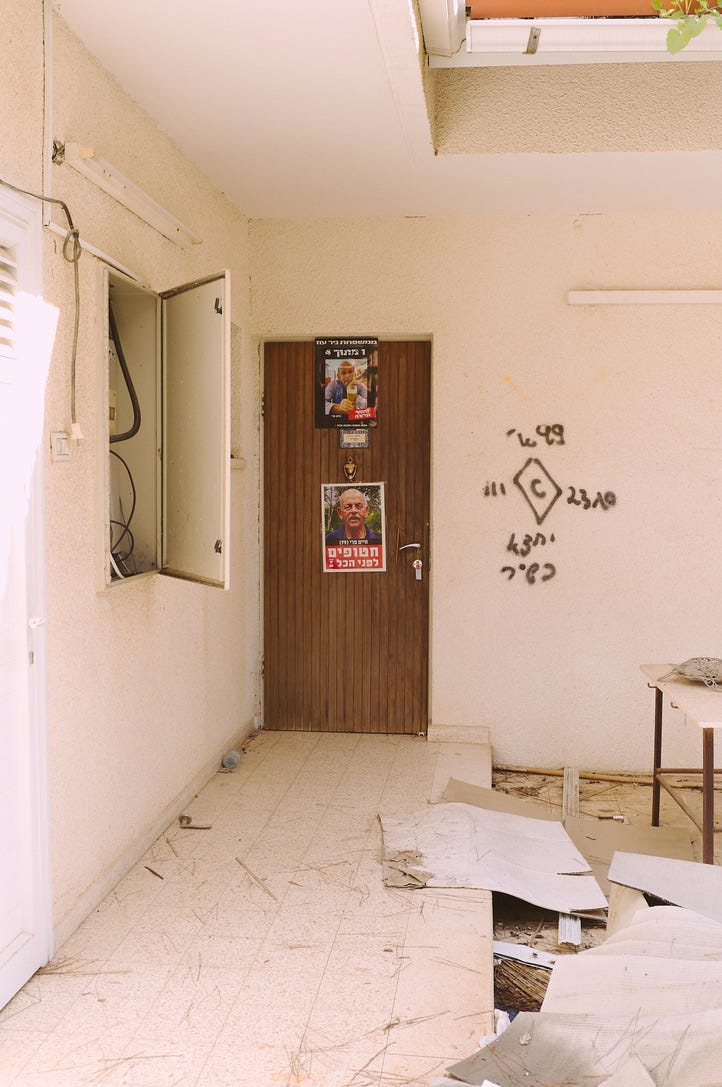

Rather than get into the stories of the 101 residents who were murdered in their own homes in the most horrific ways imaginable (all of which has been well documented), this will be more of a photo essay showing some of the devastation. Absolutely nothing could have prepared us for the emotional toll of bearing witness to this, and we will be processing the experience for a long time.

Next, we drove a few minutes through agricultural land to Kibbutz Nir Oz, a much smaller community of 400 people (pre-Oct 7), similar in design to Be’eri, but in this case organized around a paint manufacturing plant.

Nir Oz sits just over one mile from the Gaza border, and was among the first and hardest hit. Every home has a mamad, a heavily reinforced room that offers some protection against incoming missiles, and that is almost always where the children sleep in their little bunk beds. The couple who walked us through the now-mostly-empty kibbutz took us into their home, which had 17 bullet holes by the handle of their front door.

By the time that the terrorists entered, the couple had taken refuge in the children’s mamad, where their three kids (exactly the same ages as ours) had been sleeping. Since the mamads are designed to protect from missiles rather than ground incursions, the doors do not have locks. The father held the door closed for hours while they heard terrorists ransack their home, periodically trying (and failing) to break into the mamad by force. To this day, he has no idea why the terrorists didn’t just shoot him through the door. “It was a miracle.”

A total of 38 were killed and 75 were abducted into Gaza, representing about 1/3 of the tiny community. By the time we arrived at Nir Oz, Yarden Bibas, the father of the family of four kidnapped by Hamas, had been just been released. However, at the time of our visit, his wife Shira and children Kfir and Ariel, the youngest captives, remained in Gaza with no recent sign of life. When we found ourselves on the doorstep of their destroyed home, the woman guiding us through the community mentioned that Shira Bibas is one of her closest friends.

My friends in the military told me that that Shira, Kfir and Ariel Bibas had very likely been killed long ago inside Gaza. Yesterday, it was confirmed by Hamas, and today, in the middle of the largest storm in Israel since we made aliyah, their bodies are being transferred back to Israel. The mood today harkens back to the kids’ first day of school, when we learned that Ori Danino, Carmel Gat, Hersh Goldberg-Polin, Eden Yerushalmi, Alexander Lobanov, and Almog Sarusi had been executed in a tunnel, also coinciding with a massive rainstorm.

After this trauma, the kibbutz has cleared out, and about half of the residents are planning to build a new one about an hour east, a far safer distance from Gaza. Others, including adults who grew up in Nir Oz and later left to other parts of the country, are planning to rebuild and move back in, hellbent on restoring the paradise that once was.

Our hosts, however, said they would not return. “We can’t do this to our kids. It’s just too much to ask of them.” Instead, they will be settling in the new version of the kibbutz, further inland.

We rushed back to Tel Aviv to pick up Mili from preschool, reflecting on how similar these families are to ours. Every single day we see the faces of the killed and kidnapped on stickers and billboards all over the country, but being in and around their homes, in their bedrooms where they were so terribly violated, made things more visceral than I ever expected to experience them. Today will be an especially difficult one, another trough within the vicissitudes of life on The Land.